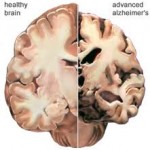

Anyone with a fear of getting Alzheimer’s disease or in the early stages of having the disease knows that severe memory loss is devastating. My own mother is sitting next to me as I write. She has a diagnosis of Alzheimer’s and I suggested a few minutes ago that I take her up to her day program for a bit of a social time. She tells me that her mind isn’t what it used to be. She’s rubbing her forehead and trying to remember who is at the program and what it will be like if she goes. She’s been to the program on about 50 different occasions. As you might imagine, I am sometimes afraid that my mind will go, just as my mother’s has, which is I suppose part of the reason I am committed to working on finding new ways to improve my brain and also helping others to do the same, via Better Brain Better Life.

Woodard’s study, recently published in the Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease (vol. 21, no. 3), took 78 healthy subjects, aged 65 and older, with an average age of 73, and subjected them to five tests: a structural MRI (sMRI) that measures the size of the hippocampal region of the brain; a functional MRI (fMRI) that shows how the brain is activated during mental tasks; a blood test that identifies the APOE ε4 allele (a known genetic marker for Alzheimer’s disease); and two standard neuropsychological tests that measure mood and ability.

The most effective combination of tests to predict near-term cognitive decline was the fMRI and the APOE ε4 test. The APOE ε4 allele alone correctly classified 61.5 percent of participants, but the combination of the ε4 allele and fMRI test correctly classified 78.9 percent of participants, including 35 percent who showed significant cognitive decline 18 months post-testing.

In an interview with Better Brain – Better Life, Woodard said he was surprised that this particular combination of two biomarkers led to such accurate predictions in healthy people. He pointed out that the two tests are relatively inexpensive and accessible. “sMRI scanners are ubiquitous in the developed world. These scanners can be retrofitted for a few thousand dollars to give them the functional component. And the fMRI test takes only five minutes and doesn’t require any special skills on the part of the subjects.”

Nevertheless, the cost/benefit ratio for the average person is not compelling at this point, says Woodard. “Our goal is come up with technology that can be used like a cholesterol blood test to predict heart disease. If we can identify those at highest risk we can put them into clinical trials and follow them over the longer term. While we have preventative treatments for heart disease in the form of statin drugs we don’t have anything comparable for Alzheimer’s at present, so identifying those who are appropriate study subjects is essential. While some of the existing drugs may slow progression it remains to be seen whether they can do so with someone who is at risk as opposed to the person with a diagnosis. “If we could delay the onset of Alzheimer’s disease by five years, we could cut the number of new cases in half. If we could delay the onset of Alzheimer’s disease by 10 years, we could potentially eliminate the disease completely.”

Larger hippocampal volume was one measure of lower risk of dementia, according to Woodard’s study. He explains that while no one knows how to increase hippocampal volume, a lot of research has been directed at how to prevent it from decreasing with age. “Physical activity is thought to play a role, as are other factors associated with stroke reduction and heart health such as diet.”

What is Woodard doing to help keep his own brain in top shape? “I take one tablespoon of high-grade fish oil daily, Vitamin D and co-enzyme Q-10. I also exercise regularly and eat a well-balanced diet.”